The cult of Mao

2015-10-20

To enter Zhang Hongtu’s exhibition at the Queens Museum in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, you need to cross the Great Wall of China.

The Chinese émigré reproduced the massive structure on the 98-foot-long wall outside his show, opening Sunday. But something is wrong with this picture. This Great Wall has doorways, lots of them. As a defense, it is useless.

Standing in the lobby gallery, Mr. Zhang proudly noted how one of doorways becomes a sort of ceremonial arch, opening the way to his biggest U.S. survey. “I like the idea that people can walk through the wall,” said the artist, a genial man with a shock of white hair.

Photoshop is the latest tool in the arsenal of the mischief-making artist, 72 years old, who has built a career out of skewering icons with deft irreverence. Soy sauce and MSG are among the materials Mr. Zhang has used to channel art traditions from East and West, along with pop culture, propaganda and his wicked sense of humor.

The artist is best known for parodic portraits of Mao, like the ones in his collaboration with designer Vivienne Tam, featured in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s recent China-focused fashion extravaganza. The Queens show offers a full picture of a pivotal figure who has become pigeonholed as “the Mao artist,” said exhibition curator Luchia Meihua Lee.

The 90 works on view, covering a half-century, show “he never stopped at one style and he never stopped challenging himself,” she said.

Mr. Zhang isn’t as renowned as later arrivals from China whose careers exploded in the ’90s art-market boom. His auction record is $187,708, for a 1989 Mao collage sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong in 2011. Prices for his works hover between about $20,000 and $60,000, said Cheryl McGinnis, a New York dealer who works with the artist. In Asia, Mr. Zhang’s exclusive dealer is Tina Keng Gallery in Taipei.

Though his profile is relatively low, his impact is considerable. Mr. Zhang became a revered role model among Chinese exiles struggling to recalibrate their artistic voices, said the Brooklyn Museum’s contemporary-art curator, Eugenie Tsai.

“He’s incredibly influential, a master of bringing together aspects of art in different cultures,” said Ms. Tsai. “He hasn’t received his due, partly because he is a modest person and won’t promote himself.”

Mr. Zhang grew up in Pingliang, a town in northwestern China. He inherited his fascination with other cultures, he said, from his father, a widely traveled Muslim who translated the Quran into Chinese and was later persecuted for his beliefs. In high school, at Beijing’s prestigious Central Academy of Fine Arts, Mr. Zhang focused on Western painting and drawing, meaning impressionism and earlier.

Some of his youthful efforts display his politically incorrect fascination with Western modernists like Henri Matisse. “I liked the strong colors and strong brush strokes,” Mr. Zhang said.

Caught up in the politics of the Socialist Education Movement, he entered Beijing’s Central Academy of Arts and Crafts, but ended up farming rice fields. Later, stuck in a government-mandated job at a jewelry-design firm, he applied to New York’s Art Students League for the sake of his work. He was granted a visa, and in 1982, left China. He has lived in Woodside, Queens for many years.

After a neo-expressionist phase in the ’80s, Mr. Zhang found a new focus after Tiananmen Square. The repression his family had experienced began reverberating in his art, not in a bitter way, but with a joyful flair that celebrated his transgression.

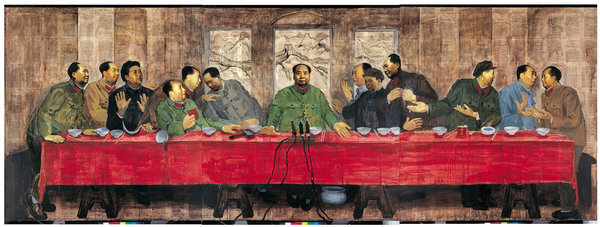

He made “Material Maos” with substances like corn, grass and dirt. He created cheeky Mao portraits in styles of Western masters like Picasso and Marcel Duchamp. He painted a Leonardo da Vinci-inspired “Last Supper” where every figure was Mao. The 1989 painting was recently acquired by the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi.

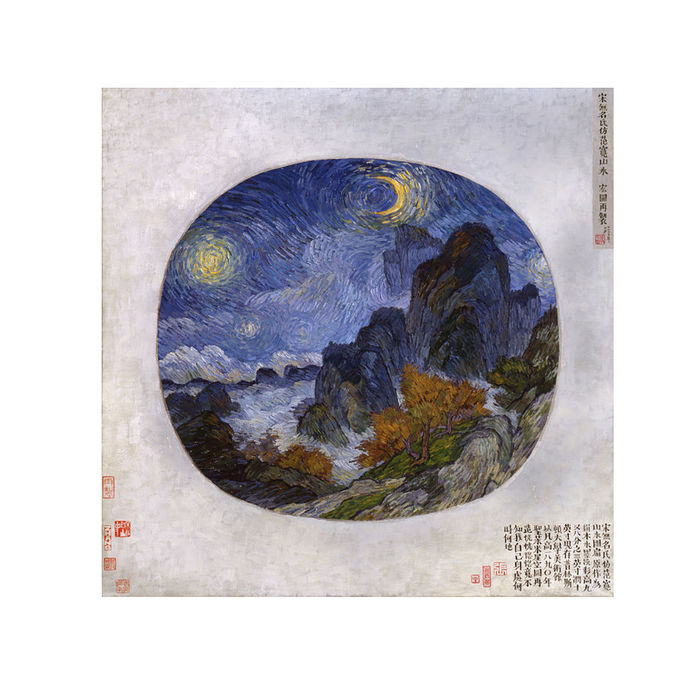

In the 1990s Mr. Zhang began exploring stylistic unions between East and West. He painted dozens of Vincent van Gogh self-portraits in traditional Chinese-ink techniques. He used soy sauce to render a mind-teasing remake of a sweatshop help-wanted ad, using traditional calligraphy.

When Ms. Tsai showed some of his stylistic mashups at the Princeton University Art Museum in 2003, she installed his Ming-style Coca-Cola bottles in the Asian galleries and his Chinese landscapes painted in the style of European masters in the Western galleries.

His technical finesse was so uncanny, she said, that curators often did a double-take: “Oh! It’s not a Monet, it’s a Zhang Hongtu!”

In a 2008 series, Mr. Zhang re-created a water album by Chinese master Ma Yuan. Mr. Zhang’s versions, though, depict the terrible beauty of dried-up riverbeds and algae buildups. The works are installed in the gallery housing a relief map of New York City’s water-supply system built for the 1939 World’s Fair.

Though Mao is gone, Mr. Zhang sees no reason to stop using his picture. “The Chinese reality has never really changed,” said the artist, who has never shown his Mao works in China. “People still worship Mao.”

That is why he cut a large Mao silhouette into his “Mao Ping Pong Table.” The game will be used in a demonstration and tournament at the museum this fall.

“If you touch the image,” said Mr. Zhang, “you lose.”

Artist Zhang Hongtu

Artist Zhang Hongtu