Domestic Interior Paintings Show How the 1% Lived in the 19th Century

2015-09-24

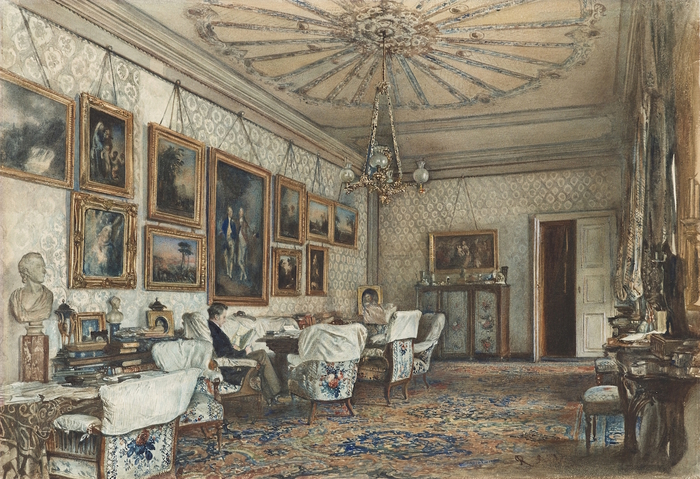

Rudolf von Alt, Salon in the Apartment of Count Lanckoronski in Vienna (possibly 1869)

Rudolf von Alt, Salon in the Apartment of Count Lanckoronski in Vienna (possibly 1869)

Photographs of immaculate, domestic interiors are common to us today, with countless images of private homes readily found in design magazines and on social media. The tradition of documenting personal rooms, however, was an exclusive one when it emerged in Europe at the start of the 19th century. Before the advent of photography, those who could afford to commissioned artists to paint small, highly detailed watercolors of the interiors of their homes that they would then slip, like photographs, into display albums. Such paintings offer a glimpse into the decadent lifestyles of the 19th century’s well-to-do and the art of recording finely decorated interior spaces. Currently, 47 such paintings are featured in House Proud, an exhibition at the Elizabeth Myers Mitchell Gallery at St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland. The exhibition was organized by the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, and the works are drawn entirely from its Thaw Collection.

“The paintings were usually made after a room had been redecorated, or they were made as mementos for royalty or their families,” curator Gail Davidson told Hyperallergic. “They would put the interiors in albums and turn the pages and reflect on their lives and what the rooms meant to them.”

Rudolf von Alt, The Library in the Apartment of Count Lanckoronski in Vienna, Riemergasse 8 (1881)

Rudolf von Alt, The Library in the Apartment of Count Lanckoronski in Vienna, Riemergasse 8 (1881)

Rudolf von Alt, “The Japanese Salon, Villa Hügel, Heitzing, Vienna” (1855)

Rudolf von Alt, “The Japanese Salon, Villa Hügel, Heitzing, Vienna” (1855)

Some parents created albums as parting gifts for their children, presented when they married and moved away so they would have physical memories of their childhood home. Families also often laid albums out on tables in drawing rooms or salons to impress their guests. Queen Victoria, who commissioned many pictures of the interiors of palaces she visited with her husband, wrote in her personal diaries that the couple enjoyed reviewing the pictures together while “thinking about their lives and what took place in these rooms,” as Davidson said.

Aristocratic families across Europe also eventually adopted the practice of commissioning these “room portraits,” as Davidson calls them. House Proud features examples of paintings from many countries including England, France, Russia, and Germany that reveal the various interior design trends of the 1800s as well as the rise of consumer culture. As people increasingly traveled across the continent, bought holiday homes in the country, and filled their residences with objects and furniture from abroad, illustrations of domestic interiors proliferated, reaching a peak around 1870.

“The practice was very much an element of the growth of the industrial classes and the development of conspicuous consumption,” Davidson said. Many of the watercolors, for example, depict interiors filled with plants and organic decorations that reflect not only an interest in the natural world but also a growing trend to own rare and exotic plants. The Villa Hügel in Venice, for example, had a Japanese salon filled entirely with decorative elements that transformed it into a garden-like space; Berlin’s Royal Palace housed a Chinese Room with murals of tropical plants and birds that also soared above the space in a ceiling painting. Rooms of that era also feature real orchids and birds in cages, which people kept not only to impress but also to entertain guests.

Josef Sotira, The Study of Czarina Alexandra Feodorovna, Russia (1835)

Josef Sotira, The Study of Czarina Alexandra Feodorovna, Russia (1835)

Many of the commissioned artists (who were mostly men) began their careers painting either topographic maps for military use or porcelain wares, but they started specializing in paintings of interiors as demand for the subject grew. Some painters even built reputations for their individual handiwork. House Proud presents paintings, for example, by Austrian brothers Rudoolf and Franz von Alt; James Roberts, a British painter who traveled with Queen Victoria; and designer Charles James — all of whom were known for their distinct styles. The approach to painting these interiors also evolved with time, gradually becoming less formal and more intimate.

“At the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th, you see a more impressionistic kind of painting,” Davidson said, “which you didn’t have earlier on in the century, where everything was much more meticulous.” Rather than adhering to a specific formula that dictated stage-like scenes, artists gradually depicted more relaxed, homely environments. Sometimes even the occupants of the buildings made appearances: the Polish Count Lanckoronski, for example, reads a book in his salon in Vienna; a girl plays the piano in a room in Hall Place, Leigh, as a dog snoozes by her side. In the foreground, someone has left a stack of newspapers folded over the frond-patterned couch. Although these paintings still largely drew attention to how people decorated their homes — from the fabrics of their furniture to what they hung on their walls to what they collected — they also sometimes resembled snapshots of daily life, curiously similar to the photographs that would gradually replace them in the early 20th century.

James Roberts, The Queen’s Sitting Room at Buckingham Palace, England (1848)

James Roberts, The Queen’s Sitting Room at Buckingham Palace, England (1848)

Henry Robert Robertson, The Interior of Hall Place, Leigh, near Tonbridge, Kent (1879)

Henry Robert Robertson, The Interior of Hall Place, Leigh, near Tonbridge, Kent (1879)

Eduard Gaertner, The Chinese Room in the Royal Palace, Berlin, Germany (1850)

Eduard Gaertner, The Chinese Room in the Royal Palace, Berlin, Germany (1850)

Eduard Petrovich Hau, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna’s Sitting Room, Cottage Palace, St. Petersburg, Russia

Eduard Petrovich Hau, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna’s Sitting Room, Cottage Palace, St. Petersburg, Russia

Anna Alma-Tadema, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s Study, Townshend House, London (1884)

Anna Alma-Tadema, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s Study, Townshend House, London (1884)

Charlotte Bosanquet, Библиотека, (1840)

Charlotte Bosanquet, Библиотека, (1840)

Karl Wilhelm Streckfuss, Artist’s Studio in Berlin (1860s)

Karl Wilhelm Streckfuss, Artist’s Studio in Berlin (1860s)