A French History of Gold, Gilded, and Fancy Frames

2015-09-28

Walk into a gallery of 17th- or 18th-century French paintings and prepare to be blinded by the gilding that encircles each work like an overwrought halo. The reigns of Louis XIII, Louis XIV, Louis XV, and Louis XVI facilitated a literal golden age of frame making centered around Paris, with carved oak and gold leaf surfaces central to the style. Earlier this month, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles opened Louis Style: French Frames, 1610–1792 in its Getty Center, with over 40 frames with and without paintings on view.

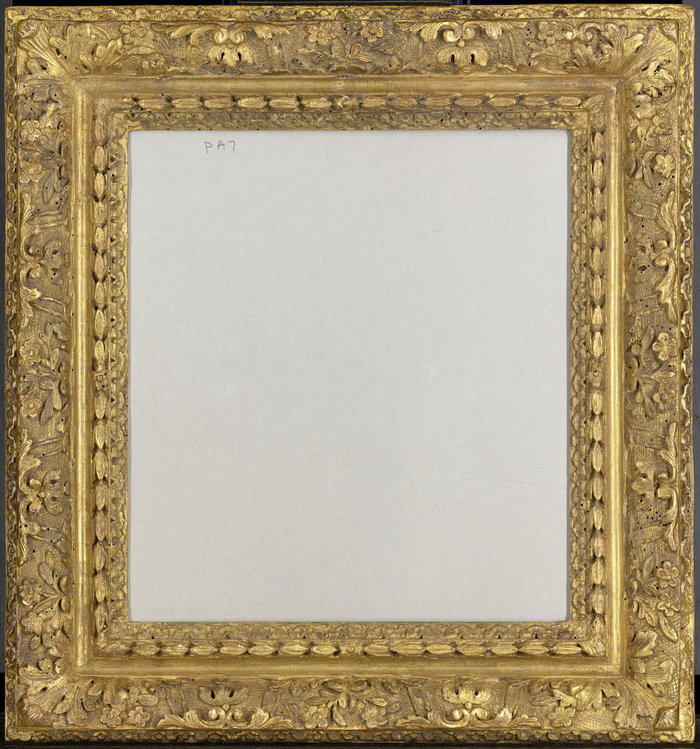

Фрагмент рамы для работы Жан-Батист Пильман, "Сценка на рынке в вымышленном восточном порту" (1764)

Фрагмент рамы для работы Жан-Батист Пильман, "Сценка на рынке в вымышленном восточном порту" (1764)

“The span of the exhibition, 1610 to 1792, is a remarkable period in which changes in style and taste — fundamentally royal style and taste — can clearly be seen to shift through the form and decoration of frames,” Davide Gasparotto, senior curator of paintings and head of the paintings department at the Getty, told Hyperallergic.

Louis XIII was fond of an Italian influence in his frames, while Louis XIV, being ostentatious in all corners of life, preferred the gilding and carving to be as elaborate as possible. Later Louis XV honed it down for more stately, but still very sculptural shapes, and finally Louis XVI favored an even more subdued aesthetic, although it all came crashing down with the French Revolution. Nevertheless, this frenzy for frames had an impact on the exhibition of art across the continent.

“In the 18th century, French style, including its embodiment in frames, was emulated and acquired as the epitome of taste all over Europe,” Gasparotto explained. “During the 19th century, following the Napoleonic period, 18th-century styles were celebrated through revival treatments, particularly the lavish Louis XV mode. Significantly, even the earliest Louis style — the flat leaf acanthus moldings of Louis XIII — were eagerly sought in the last decades of the 19th century by Impressionist painters, notably Claude Monet, to surround his paintings.”

Gasparotto noted that a paradox of a good frame is it “‘disappears’ from our view.” Louis Style includes an interactive component where visitors can try to choose the right frame for paintings at the Getty. The museum itself has recently focused on acquiring historically appropriate frames for its paintings, many of which are in this exhibition. While some museumgoers might notice different frames for different periods of art, most people overlook this decorative art tradition. However, the National Gallery in London just closed an exhibition on Sansovino frames from 19th-century Venice, and last year the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow hosted an exhibition on the history of frames in Russian art.

“Frames are essential to the presentation of a painting, certainly those in our collection of European paintings executed before 1900,” Gasparotto stated. “They have the capacity to enhance or distract from a picture’s visual impact and even affect the relationship of a painting to its surroundings.”

Installation view of ‘Louis Style’

Installation view of ‘Louis Style’

Hyacinthe Rigaud, “Charles de Saint-Albin, Archbishop of Cambrai” (1723), oil on canvas (courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Hyacinthe Rigaud, “Charles de Saint-Albin, Archbishop of Cambrai” (1723), oil on canvas (courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Maurice-Quentin de La Tour, “Portrait of Gabriel Bernard de Rieux” (1739–41)

Maurice-Quentin de La Tour, “Portrait of Gabriel Bernard de Rieux” (1739–41)

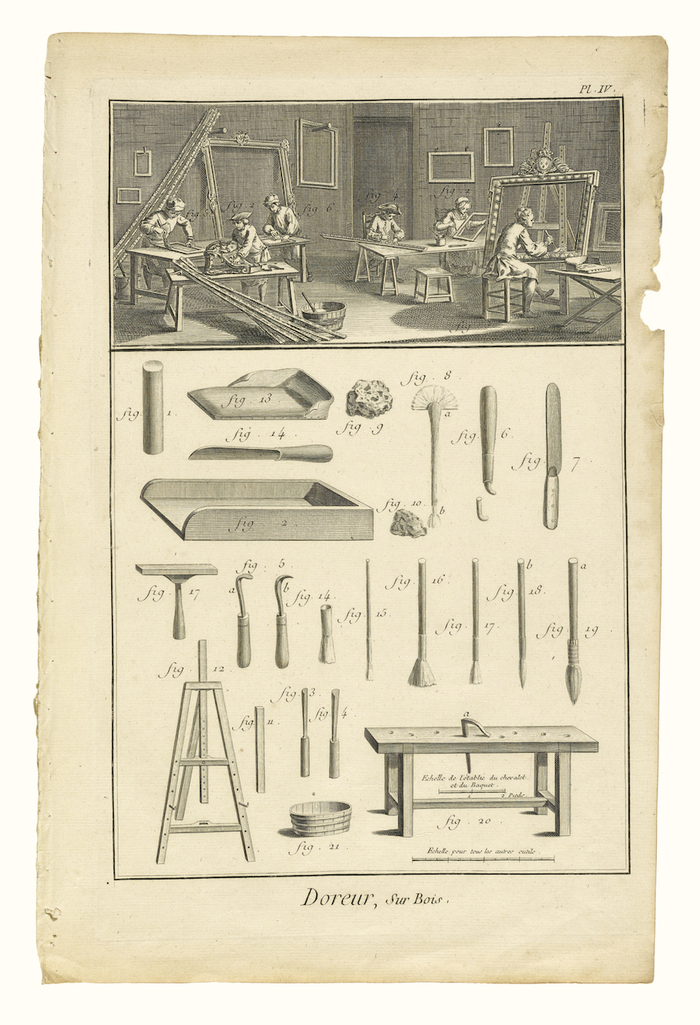

J. R. Lucotte, Louis-Jacques Goussier, Benoît-Louis Prévost, Denis Diderot, and Jean le Rond d’Alembert, “Doreur, sur Bois” (1751–76), etching

J. R. Lucotte, Louis-Jacques Goussier, Benoît-Louis Prévost, Denis Diderot, and Jean le Rond d’Alembert, “Doreur, sur Bois” (1751–76), etching