Kehinde Wiley Paints the Precariousness of Black Life

2015-06-01

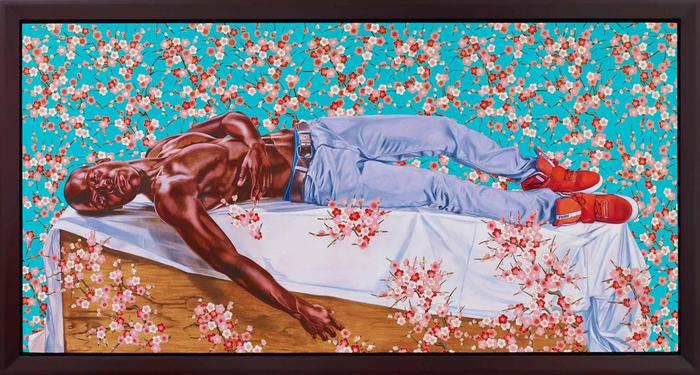

Installation view, ‘Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic’ at the Brooklyn Museum, with “Bound” (2014) in the center (photo by Jonathan Dorado, courtesy Brooklyn Museum)

Installation view, ‘Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic’ at the Brooklyn Museum, with “Bound” (2014) in the center (photo by Jonathan Dorado, courtesy Brooklyn Museum)

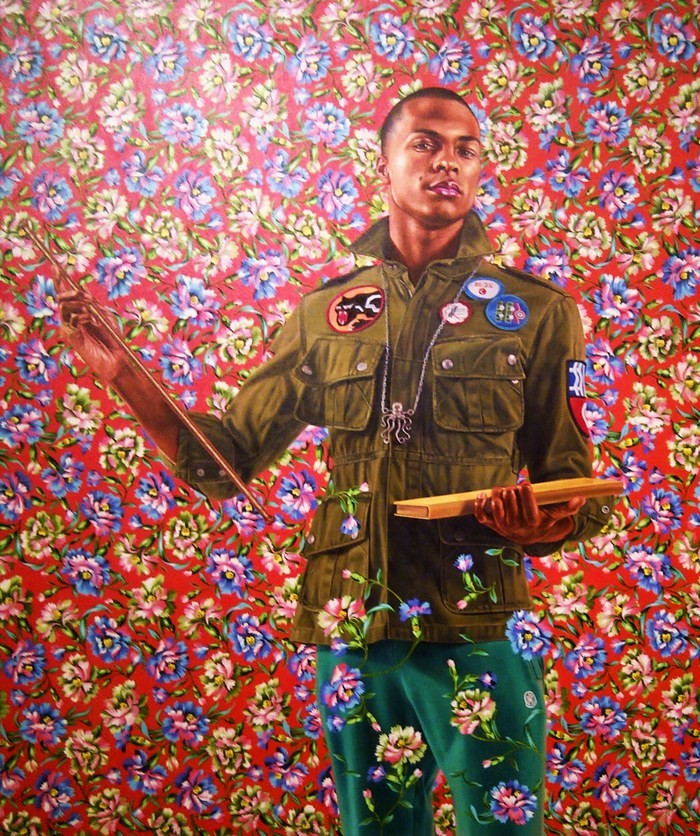

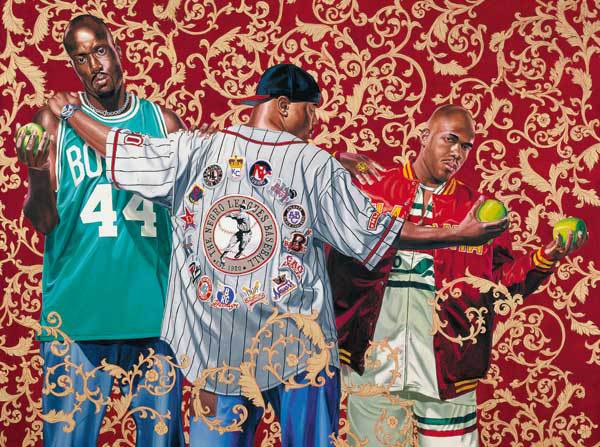

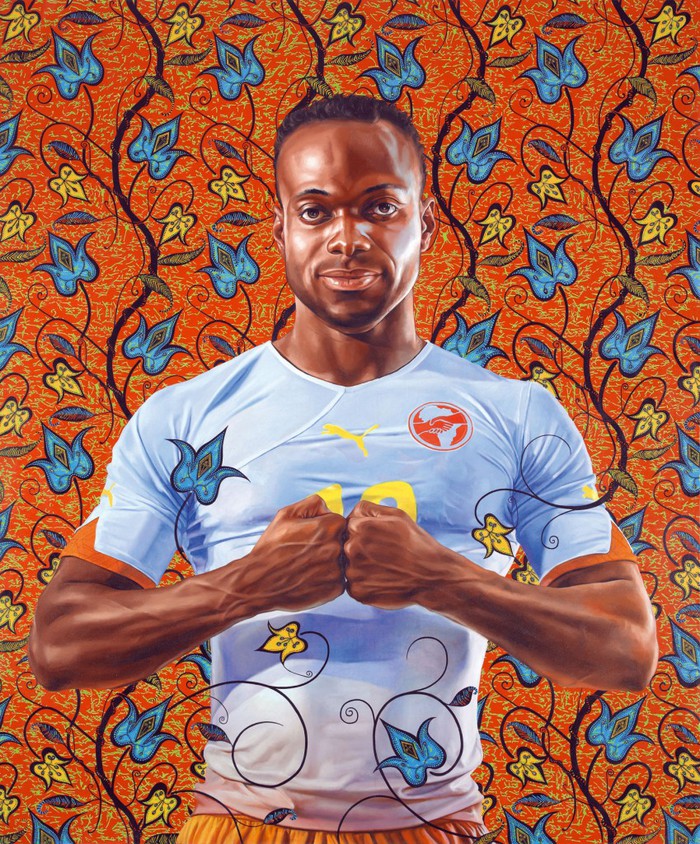

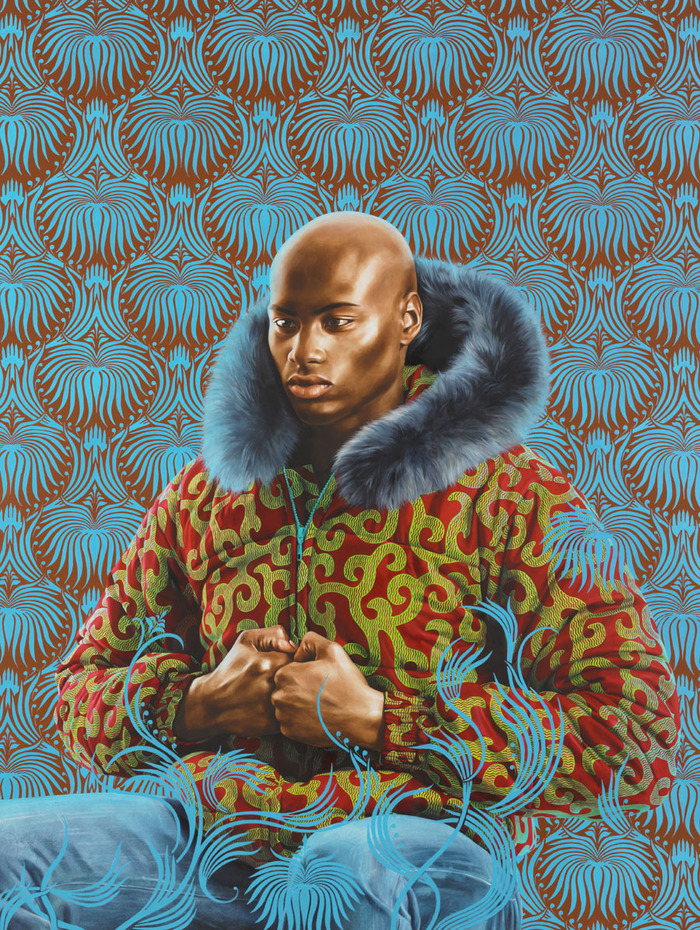

Much has been made of the current Kehinde Wiley retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum. We know the story well: daunted by the dearth of black figures in the art historical canon, Wiley reclaimed the regality and revelry in European painting, but superimposed young black men cast from the street onto backdrops of floral patterns often taken from 19th-century botanical drawings or Dutch wax prints — abstracted images of global imperial pursuit. From the streets of Harlem, Dakar, Tel-Aviv, and Kingston, Wiley has painted a narrative of marginal black bodies traversing the annals of time but speaking specifically to the present. He has also been heavily criticized for his thinly veiled surfaces, factory modes of production, and his complicity in the extreme capitalism of the art market.

Kehinde Wiley, “The Sisters Zénaïde and Charlotte Bonaparte” (2014), oil on linen, 83½ x 63 in (212 × 160 cm)

Kehinde Wiley, “The Sisters Zénaïde and Charlotte Bonaparte” (2014), oil on linen, 83½ x 63 in (212 × 160 cm)

Up until 2012, when he began the series An Economy of Grace, Wiley was reproved as well for the absence of women in his triumphant recuperation of black representational space. At the Brooklyn Museum this critique is addressed, somewhat, through the inclusion of his more recent images of black female figures, though they are cloistered in the final substantial gallery of the retrospective. Works like the large-scale bronze “Bound” (2014) and the stunning painting “The Sisters Zénaïde and Charlotte Bonaparte” (2014) drive home the gender politics of the retrospective’s installation — the way these works of art featuring women, when read solely along gender lines, remain separate from his more well-known male portraits. Through the insertion of black women in the Bonaparte painting, for example, we may observe the conceptual binding of the regal legacy of the Bonapartes and the troubled fate of contemporary Haiti together; not beholden to Jacques-Louis David, Wiley poses these young women in full view, yet these important nuances are lamentably left for viewers to discern. Wiley might understand the history of Western art as one tussled over by great male virtuosos, but his women speak volumes about historical blindspots — and suggest a missed opportunity to open up new but difficult conversations about the exhibition’s restraint in contextualizing Wiley’s own complicity in systems of patriarchy for what seems to be the greater good of black representation.

Still, one can’t deny curator Eugenie Tsai’s admirable efforts in producing a democratic interpretative strategy for Wiley’s work. Her curatorial team commissioned wall texts from dozens of thinkers, curators, and scholars in the field of art history, from Kobena Mercer to Naomi Beckwith, all of whom receive credit for authoring the didactic texts and providing personal takes on the artworks. Some of the more successful interpretations move to abandon the narrative of art history and Wiley’s appropriative gestures all together, in order to account for other dissonances which emerge. Such is the case for cultural critic Touré, who rightly points to the way in which Wiley’s investigations of wanted posters in Mug Shot Studies, from 2006, eerily bring us back to the present of racial profiling and inequity. Wiley, he writes, “saw not a criminal but a cherub.”

Installation view, ‘Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic’ at the Brooklyn Museum, showing Wiley’s ‘Memling’ series

Installation view, ‘Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic’ at the Brooklyn Museum, showing Wiley’s ‘Memling’ series

Kehinde Wiley, “Saint Ursula and the Virgin Martyrs” (2014), stained glass

Kehinde Wiley, “Saint Ursula and the Virgin Martyrs” (2014), stained glass

Works like these, paired with recent high-profile instances of police brutality and racial tension (more phenomena concerning the politics of visibility), indicate how much we should be running, not walking, to reexamine A New Republic before it closes this weekend.

Kehinde Wiley is one of the most commercially successful artists of our time. Wiley’s young black men are largely traded by the hands of the white art world elite, from the private collection to the art gallery to the museum. The politics of placement and spectacle demand an examination here, inasmuch as these are all discursive fields in which blackness is largely contained, kept at bay, or even erased. To set up an exhibition in which the black male body functions as the spectatorial premise is not only to reclaim a simulacrum of a European painting tradition; it is also to create a confrontation of metanarratives and ideologies that are ever-present outside the walls of the museum. That is, when you enter into the space of the exhibition, you see not just these multilayered offerings of queerness and blackness built into a critique of art historical discourse; you could very well see a barrage of Mike Browns, Eric Garners, Walter Scotts, and most recently, Freddie Grays, too. (Or you could think about the stories of brutalized black women that remain underreported in the Black Lives Matter movement, as Kali Nicole Gross notes in a recent article for the Huffington Post.)

And so there is a productive discomfort in the hinging of Wiley’s unreality to the pressing reality of the precariousness of black life that persists outside the museum walls. When is the last time we’ve seen such a metapolitical choreography of interpolating systems of capitalism, subjectivity, representation, and histories of colonialism and domination unfold within a major New York museum? To witness droves of museumgoers — young, old, black and white — sharing in the beauty and discomfort of Wiley’s provocations is a rare opportunity. If anything, A New Republic interrogates the fleeting possibility of humanity underneath all the work’s grandeur. And yet, Wiley’s muses, taken together, seem to construct a postmodern mausoleum.

Kehinde Wiley in his studio

Kehinde Wiley in his studio